Summary. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change will convene its next conference at Durban , South Africa December 9, 2011 . The conference will consider topics contained in the Cancun Agreements from last year’s meeting. These include mitigation of global warming, adaptation to harmful effects arising from global warming, reducing emissions by slowing or reversing deforestation, codifying the trustworthiness of emissions data, and establishing funding to help developing countries implement mitigation and adaptation measures.

It is predicted that the world will continue to emit increasing amounts of carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, by burning fossil fuels, in the absence of policies that limit these emissions. Increased atmospheric carbon dioxide will exacerbate global warming and its harmful effects. Most of the increasing emissions rate originates from developing, rather than from developed, countries. Yet major emitters among developing countries have not put forward policies to limit the absolute amount of their emissions. U. S. Special Envoy for Climate Change Todd Stern has recognized this problem as a legacy approach from two decades ago that is no longer valid today.

The Durban Conference should address the distinction in predicted emissions rate between developed and developing nations. It should make progress toward implementing a worldwide program directed toward limiting greenhouse gas emissions by all nations of the world.

Introduction. The world’s environmental and political leaders will convene the 17th conference under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) from November 28 to December 9, 2011 in Durban , South Africa

The Cancun conference addressed the following issues:

- efforts at mitigation of the increasing emission of greenhouse gases around the world (i.e., reducing the rate of such emissions);

- efforts at adaptation to the adverse effects, past and future, of global warming;

- reduction of emissions coming from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries;

- assuring transparency of knowledge and information concerning efforts at mitigation and adaptation by establishing standards for measuring and reporting data, and verification of results; and

- establishing an international fund to support mitigation and adaptation efforts in developing and least developed countries.

The Cancun Agreements were the final product (text and press release; see the Cancun meeting web site for additional documents) of the conference, and were approved by all the parties except one. As such, they reflect affirmative commitments by all the parties going forward to objectives and concrete steps to be taken.

A signal feature of the Agreements is the explicit acknowledgement by all the participants that “climate change represents an urgent and potentially irreversible threat to human societies and the planet, and thus requires to be urgently addressed by all Parties”, and that they must strive to constrain the average global rise in temperature to 2º C (3.6º F) or less. It states that “deep cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions are required according to [climate] science”, as documented in the Fourth Assessment Report of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change” (IPCC), which was issued in 2007. It thus established an upper limit for the average global temperature in order to prevent severe consequences from afflicting the planet.

Commitments under the Cancun Agreements. The following are among the commitments made in the Agreements.

Mitigation. The developed, or already industrialized, countries (such as the U. S. Europe , and others) were encouraged to develop more ambitious targets for reducing man-made greenhouse gas emissions as recommended by the IPCC. They are to report their inventories of greenhouse gas emissions every year, and to report on progress toward reducing emissions, as well as on financing and adaptation activities, every two years.

In order to promote and enable mitigation efforts by developing countries (such as China India

Reduction of emissions due to deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) is a major undertaking in the Cancun Agreements. Reversing deforestation and new planting of trees for restoring forests is a significant feature of the Agreements.

Adaptation. Among other measures, the Agreements establish a Cancun Adaptation Framework, an organization that will oversee both the substance and the financing of projects that help least developed countries adapt to the adverse effects of global warming. These include sea level rise, increasing temperatures, and ocean acidification, among others.

Transparency. A major impediment to progress in addressing global warming at the level of a global conference had been a perceived or suspected lack of credibility when a particular nation reports its emissions, and its mitigation and adaptation activities. The Cancun Agreements established formal mechanisms for assuring transparency in the measurement, reporting, and verification of activities in these areas.

Financing. The Cancun Agreements established objectives for financing adaptation and mitigation efforts among poorer nations of the world. A fast start financing round from industrialized countries was to achieve a committed level of $30 billion by 2012. It further establishes a long-term goal of providing $100 billion/yr by 2020.

Actions by Parties Since the Cancun Conference

Developed countries submitted emission reduction targets to the UNFCCC, which reported them in June 2011. Goals from a selection of developed countries/regions for the year 2020 are included in the following table.

Country/Region | Reference year | Reduction goal, % | Comments |

2000 | 25 | Contingent on agreement by world’s nations to limit CO2 to 450 ppm; otherwise lower goals undertaken unilaterally | |

2005 | 17 | Contingent on | |

European Union | 1990 | 20 | Reaffirmed commitment to limit global warming to 2ºC. Confirmed effort to reduce emissions by 80-95% by 2050. |

1990 | 25 | Premised on international agreement for reduction by all major economies. | |

1990 | 15-25 | Conditioned on all major emitters honoring their emissions obligations, and allowance for effects of domestic forests. | |

U. S. | 2005 | 17 | Assumes passage of climate legislation. Assumes other developed, and advanced developing countries, submit mitigation actions. |

Developing countries undertook to provide an assessment of help, finances and technologies that the developed countries would provide in order to help them to break from “business as usual” (current economic activities in the absence of climate change plans), and permit progress in achieving reductions in the rates of emissions. Developing countries also undertook to put in place rigorous emissions measuring, reporting and verification practices, also to be transmitted to the UNFCCC.

Developing countries, on a voluntary basis, submitted “nationally appropriate mitigation actions” planned for coming years to the UNFCCC. Plans from only 45 countries were deposited as of 18 March 2011 . Interestingly, many countries with smaller economies enumerated detailed goals and steps, while countries that are major emitters of greenhouse gases provided only brief, more generic, statements of goals. A selection from among these larger economies is presented in the table below.

Country | Year for goal | Statement of goal |

2020 | Expected emissions reduction of between 36.1 and 38.9 % below the level predicted with no actions taken. Detailed listing of contributing actions provided. | |

2020 | Voluntary measures to reduce CO2 emissions per unit of gross domestic product ( | |

2020 | Voluntary efforts to reduce emissions intensity of its | |

2020 | Voluntary efforts to reduce emissions by 26% by, among others, lowering the deforestation rate, energy efficiency, developing low-emitting transport means and renewable energy sources. |

Importantly, in the table above the goals expressed by China and India are given in terms of emissions intensity, the amount of greenhouse gas emissions needed to produce a unit of economic product. While the goals of these nations may be to reduce their emissions intensities, they remain at liberty, by their statements of voluntary policies, to increase the absolute amount of their emissions. These will increase as they expand their economies and strive to achieve higher standards of living for their people. This feature is a crucial characteristic of the “firewall” between developed and developing countries, considered below in the section on Todd Stern’s remarks.

The Kyoto Protocol included a Clean Development Mechanism, whereby developed countries can contribute to their own reductions in emissions by establishing an emissions-reducing project in a developing country. Included in this objective is to be an evaluation of carbon capture and storage as a means of preventing CO2 produced from fossil fuels to enter the atmosphere; these developments are intended to be discussed at the Durban conference, and hopefully finalized. The Cancun agreement also set forth objectives for putting in place policies on land use, land-use change and forestry, including establishing forestry baselines for future reference. These and related Kyoto-derived objectives, enumerated in the Cancun agreement of 2010, are to be considered further at Durban

Financing was discussed in the November 5, 2011 issue of The Economist. Although Cancun proposed establishing a Green Climate Fund, The Economist points to a report from the Climate Policy Initiative, which finds that climate funding is already flowing, currently at almost US$100 billion a year, with more than half coming from private sources and relatively little directly from governments. Much of this funding was already under way prior to the Cancun Agreements.

Todd Stern, the Special Envoy for Climate Change in the U. S. State Department, gave a realistic view of current international climate negotiations in his Statement presented to the U. S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs on May 25, 2011 (accessed Nov. 8, 2011). He pointed out a glaring difficulty in UNFCCC negotiations, and in the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 resulting from it, as a legacy paradigm enshrined since about 1992, namely, that these agreements established a “firewall” (Mr. Stern’s characterization) between developed and developing countries. The firewall ensures that only developed countries be required to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, while developing countries would be free to pursue development without being bound to lower their emissions. Developing countries were not required to abide by Kyoto United States Kyoto

Mr. Stern pointed out that the world has changed drastically since the early 1990s, such that the original distinctions no longer make sense. As of 2009, 4 of the highest 10, and 9 of the highest 20 emitters of CO2 resulting from burning fossil fuels were developing countries (including China China GDP has grown to be nearly 6 times larger than in 1992, its per capita GDP is more than 5 times larger, its CO2 emissions are nearly 3 times larger and its per capita CO2 emissions are 2.5 times larger. In contrast, over this time economic growth and increases in emissions from developed countries were far more gradual (see below).

The Copenhagen Cancun and Durban U. S. China India U. S.

Developing countries have espoused, during the course of negotiations, a policy of reducing their emissions intensities, as noted above. Mr. Stern noted, however, that even while developing countries progress to using energy more efficiently during their development, they still continue to increase the absolute quantity of their emissions as their economies grow. In Mr. Stern’s view, extending the Kyoto Protocol is “unworkable”. The parties should not confront the global climate challenge by “focusing only on developed countries when developing countries already account for around 55% of global emissions and will account for 65% by 2030”. He pointed out that China U.S.

Mr. Stern outlined a new policy developed by the U. S. U. S. U. S.

CO2 Emissions Rate Continues to Climb. According to a report by Reuters dated June 8, 2011 (accessed November 10, 2011 ), China U. S. China India

Global Warming Continues. Excessive greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere are understood to cause an increase in long-term global average temperatures. The U. S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported that 2010 tied with 2005 as being the hottest year on record (accessed November 10, 2011 ). This assessment was confirmed by the U. S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (accessed November 10, 2011 ). In addition, 2010 had the highest recorded global average amount of precipitation.

Projected Future Energy Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The U. S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) issued its report, International Energy Outlook 2011 (designated IEO 2011 here), on Sept. 19, 2011 (for a summary see this post. The report presents historical worldwide energy usage data to 2008 and forecasts worldwide energy usage from 2008 through 2035. IEO 2011 frequently divides the world into countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD; United States, Canada, Mexico, Chile, most European countries, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand; here considered developed), and non-OECD countries, including China, India, Russia, Brazil, the Middle East and Africa (here considered developing).

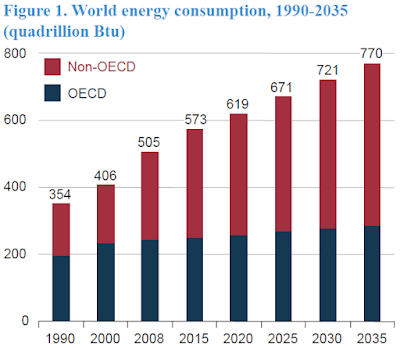

IEO 2011 envisions an overall increase of 53% in yearly world energy usage by 2035 in the absence of any policies limiting use of fossil fuels, based on the amount used in 2008 (see Figure 1), with half of that increase originating in China India

Annual usage of energy in all forms for certain years between 1990 and 2035. The horizontal spacing of the bars is not linear; the interval at the left is 10 years, while the interval after 2015 is every 5 years.

Source: U. S. EIA International Energy Outlook 2011 http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/ieo/pdf/0484(2011).pdf

use more than doubles in this period. Predicted energy consumption by non-OECD countries increases by 85%, whereas OECD nations use only 18% more energy in this time period.

The energy use shown in Figure 1, being mostly derived from fossil fuels, necessarily produces emissions of CO2 into the atmosphere when the fuels are burned. The actual and predicted emissions of CO2 before and after 2008, respectively, are shown in Figure 2. Most of the growth in emissions comes from developing countries, for which emissions

Worldwide emissions of CO2 for (left panel, Figure 110) developed (OECD) and developing (Non-OECD) nations, and by fossil fuel used (Liquids is primarily petroleum and its products). The line at 2008 separates actual data (on the left) and predicted emissions (on the right) assuming no policies limiting emissions are in place.

Source: U. S. EIA International Energy Outlook 2011 http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/ieo/pdf/0484(2011).pdf

increase by 73% by 2035 over the 2008 level of emissions (Figure 2, left panel). For developed countries, this increase is only 6%. Worldwide, the emissions from coal increase the greatest, from 39% of the total in 1990, to 43% of the total in 2008, and 45% of the total in 2035. Much of this arises from China India

Joeri Rogelj and coworkers, in an article published in Nature Climate Change Vol.1, pp. 413–418 Year (2011), warned of the high likelihood that the limits on emissions of CO2 required to keep the long-term global average temperature within the 2ºC limit confirmed in the Cancun Agreements might not be attained, but that this limit would be exceeded. These authors re-examined the results of many model projections of greenhouse gas emissions, using a risk-based analysis. They concluded that of those models, the ones showing a greater than 66% likelihood for conforming to this temperature limit required emissions to peak between 2010 and 2020, and to fall significantly after that. They conclude “Without a firm commitment to put in place the mechanisms to enable an early global emissions peak followed by steep reductions thereafter [including by several major emitters], there are significant risks that the 2 °C target, endorsed by so many nations, is already slipping out of reach.”

Conclusion. The world’s nations continue to emit CO2 by burning fossil fuels to fulfill their energy needs. Emissions in future years are predicted to continue increasing by about 2% per year in the absence of policies which would limit burning of fossil fuels and lower the rate of greenhouse gas emissions. Among developed countries, the European Union in fact has embarked on a region-wide program to lower emissions drastically by 2050. The U. S. California

In contrast, two of the main developing countries, China India

This situation illustrates the persistence of the legacy paradigm identified by U. S. Special Envoy Todd Stern, of the firewall concerning greenhouse gas emissions separating developed from developing countries. This fundamental difference of opinion remains as perhaps the most important issue to be resolved at a global level, as the UNFCCC has convened its Conferences of the Parties over the years. The parties of the UNFCCC have to come together to limit worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, ultimately to near zero. Let us hope that progress toward this objective can be made at the Durban Conference.

© 2011 Henry Auer

No comments:

Post a Comment