The European

Union confirms the next milestone along its energy Roadmap. The nations of the world are working

toward establishing a new climate treaty by late 2015 that would lower future

greenhouse gas emissions (among other provisions). Independently, the European

Union (EU) agreed to a significant goal in reducing

emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) on October 23, 2014 . The

EU is a supranational organization of 28 member nations. As detailed below, it has had policies in

place for almost a decade to reduce GHG emissions. The new pronouncement extends its timelines

and codifies goals it had already established earlier. Specifically, the EU agreed to lower GHG

emissions by 40% below the emission levels of 1990 by 2030. The goals also include achieving a 27% share

of energy from renewable sources, and increasing energy efficiency by 27%.

Emission Trading

Scheme. The EU began

implementing policies to reduce GHG emissions as the Kyoto Protocol (KP) became

effective. Even before KP entered into

force the EU created its Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) in 2005

in preparation for entering under its emissions restrictions. The ETS is a cap-and-trade regime covering over

11,000 major fixed sources of GHG emissions, both governmental and

corporate. Unfortunately, for much of the

time since then the ETS has failed effectively to set a market price for GHG

emissions that would succeed to lower emissions. Initially, too many allowances for emission

were issued, so that their price tumbled.

As this was corrected, the Great Recession reduced economic activity,

lowering demand for energy, again pressuring the price for allowances to

fall. As recently as 2013 the European

Parliament temporarily suspended marketing new allowances.

The deliberations leading to the new declaration also had contentious issues

. Reducing emissions of carbon dioxide

(CO2), the most prevalent GHG, affects coal-burning generating

plants most severely because use of coal emits almost twice as much CO2

as does burning a fuel such as natural gas.

Countries in the EU heavily reliant on coal for electricity, such as Poland United Kingdom Germany Fukushima

The new declaration

keeps the EU within its overall timeline for long-term, major reductions in GHG

emissions according to its energy Roadmap (see below). But several environmental scientists and commentators consider the

plan to be inadequate to achieve the stringent Roadmap objective in 2050. They are concerned that the plan would leave

too much of the intended reduction in emissions to be achieved later, in the

two decades between 2030 and 2050, an achievement that may challenge the best

technologies and policies available. For

example, Richard Black, the director of the British Energy and Climate

Intelligence Unit, a nonprofit organization, doubted that this plan would “allow the E.U. to meet its long-term target of virtually

eliminating carbon emissions.”

Background

The countries of

the world currently face highly disparate energy situations and climate

environments. Their different conditions

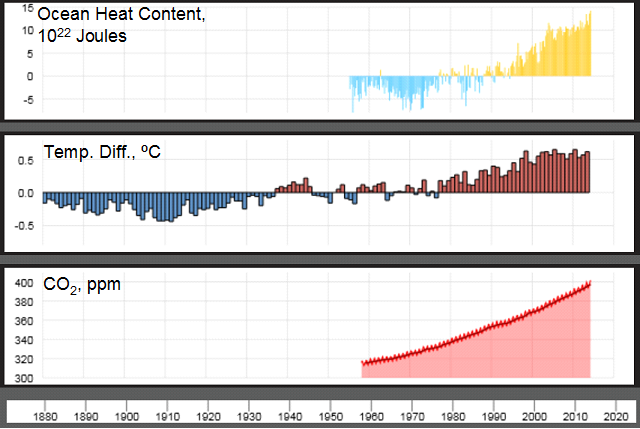

color their outlook as the world faces the problem of global warming brought on

by humanity’s use of fossil fuels for energy.

In developed nations, which have benefited from the industrial

revolution since its early days, citizens are comfortable with the lifestyle

that abundant energy affords them. Many

are reluctant to change their ways to reduce emissions.

Developing nations,

on the other hand, have been applying energy-intensive technologies to expand

their economies only in recent decades, desiring to catch up to the developed

countries in relatively unconstrained fashion.

Their people too are reluctant to move away from fossil fuels to fulfill

their growing energy needs.

Impoverished

countries and island nations experience the harms brought on by global warming

for which they have not been responsible.

Their citizens hunger for the benefits that wider energy use could

provide; those in island nations face encroaching seas as land-based ice sheets

continue melting.

The United

Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has scheduled periodic global

climate reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change since

1990. The UNFCCC led to negotiation of

the Kyoto Protocol (KP) in 1997. KP

required developed countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but excluded

developing and impoverished countries from coverage. KP entered into force in 2005 after the

requisite number of countries ratified it (the U. S.

Source:

“A Roadmap for moving to a competitive low carbon economy in 2050”, broken down by economic sector. European

Commission, March 8, 2011 ;

Interim milestones were

established for reductions in emission rates of 7% by 2005, 20% by 2020, and

40-44% by 2030. The European Environment Agency determined in 2013

that the EU is on track to achieve the 2020 milestone. Renewable fuel use had climbed to 14% of

total energy consumption. About

two-thirds of this originates from burning biomass and waste; in Sweden Austria Denmark Portugal Cyprus Spain

The EU is the

most proactive region among

developed countries in establishing policies to lower emission rates of

GHGs. The U. S.

Emissions from

the developed countries of the world

considered as a group have been relatively unchanged in recent years, and are

projected to continue that trend (see the graphic below).

Annual rates of energy usage for

Source: U. S. Energy Information Administration; http://www.eia.gov/pressroom/presentations/sieminski_07252013.pdf (slide 5).

Conclusion

The declared

intention of the European Union to continue meeting its milestones under the

energy Roadmap to 2050 is a major contribution to mitigating worldwide GHG

emissions. Similarly the executive

actions taken by the U. S. China India Copenhagen Cancun (2010) conferences of the UNFCCC. The nations of the world must succeed in

these negotiations.

© 2014 Henry Auer